Language family

A language family is a group of languages related by descent from a common ancestor, called the proto-language of that family. The term comes from the Tree model of language origination in historical linguistics, which makes use of a metaphor comparing languages to people in a biological family tree or in a subsequent modification to species in a phylogenetic tree of evolutionary taxonomy. All the apparently biological terms are used only in the metaphoric sense. No real biology is included in any way in the metaphor.

As of early 2009, SIL Ethnologue catalogued 6,909 living human languages.[1] A "living language" is simply one that is in wide use as a primary form of communication by a specific group of living people. The exact number of known living languages will vary from 5,000 to 10,000, depending generally on the precision of one's definition of "language", and in particular on how one classifies dialects. There are also many dead and, distinct from dead, extinct languages.

Membership of languages in the same language family is established by comparative linguistics. Daughter languages are said to have a genetic or genealogical relationship; the former term is more current in modern times, but the latter is equally as traditional.[2] The evidence of linguistic relationship is observable shared characteristics that are not attributed to borrowing. Genealogically related languages present shared retentions, that is, features of the proto-language (or reflexes of such features) that cannot be explained by chance or borrowing (convergence). Membership in a branch or group within a language family is established by shared innovations; that is, common features of those languages which are not attested in the common ancestor of the entire family. For example, what makes Germanic languages "Germanic" is that they share vocabulary and grammatical features which are not believed to have been present in Proto-Indo-European. These features are believed to be innovations that took place in Proto-Germanic, a descendant of Proto-Indo-European that was the source of all Germanic languages.

Contents |

Structure of a family

A family is a phylogenetic unit; that is, all its members derive from a common ancestor, and all attested descendants of that ancestor are included in the family. However, unlike the case of biological nomenclature, every level of language relationship is commonly called a family. For example, the Germanic, Slavic, Romance, and Indic language families are branches of a larger Indo-European language family.

Subdivision

Language families can be divided into smaller phylogenetic units, conventionally referred to as branches of the family because the history of a language family is often represented as a tree diagram. However, the term family is not restricted to any one level of this "tree". The Germanic family, for example, is a branch of the Indo-European family. (In this way, the term family is analogous to the biological term clade.) Some taxonomists restrict the term family to a certain level, but there is little consensus in how to do so. Those who affix such labels also subdivide branches into groups, and groups into complexes. The terms superfamily, phylum, and stock are applied to proposed groupings of language families whose status as phylogenetic units is generally considered to be unsubstantiated by accepted historical linguistic methods.

Dialect continua

Some closely knit language families, and many branches within larger families, take the form of dialect continua, in which there are no clear-cut borders that make it possible to unequivocally identify, define, or count individual languages within the family. However, when the differences between the speech of different regions at the extremes of the continuum are so great that there is no mutual intelligibility between them, the continuum cannot meaningfully be seen as a single language. A speech variety may also be considered either a language or a dialect depending on social or political considerations, as in the case of Hindi and Urdu within Hindustani. Thus different sources give sometimes wildly different accounts of the number of languages within a family. Classifications of the Japonic family, for example, range from one language (a language isolate) to nearly twenty.

Proto-languages

The common ancestor of a language family is seldom known directly, since most languages have a relatively short recorded history. However, it is possible to recover many features of a proto-language by applying the comparative method—a reconstructive procedure worked out by 19th century linguist August Schleicher. This can demonstrate the validity of many of the proposed families in the list of language families. For example, the reconstructible common ancestor of the Indo-European language family is called Proto-Indo-European. Proto-Indo-European is not attested by written records, since it was spoken before the invention of writing.

Sometimes, though, a proto-language can be identified with a historically known language. For instance, dialects of Old Norse are the proto-language of Norwegian, Swedish, Danish, Faroese and Icelandic. Likewise, the Appendix Probi depicts Proto-Romance, a language almost unattested due to the prestige of Classical Latin, a highly stylised literary register not representative of the speech of ordinary people.

Other classifications of languages

Isolate

Most of the world's languages are known to belong to language families. Those that have no known relatives (or for which family relationships are only tentatively proposed) are called language isolates, which can be thought of as minimal language families. An example is Basque. It is generally assumed that most language isolates have relatives, but at a time depth too great for linguistic comparison to recover.

Languages that cannot be reliably classified into any family are known as language isolates. A language isolated in its own branch within a family, such as Armenian within Indo-European, is often also called an isolate, but the meaning of isolate in such cases is usually clarified. For instance, Armenian may be referred to as an Indo-European isolate. By contrast, so far as is known, the Basque language is an absolute isolate: it has not been shown to be related to any other language despite numerous attempts, though it has been influenced by neighboring Romance languages. A language may be said to be an isolate currently but not historically, if related but now extinct relatives are attested.

Sprachbund

Shared innovations acquired by borrowing or other means, are not considered genetic and have no bearing with the language family concept. It has been asserted, for example, that many of the more striking features shared by Italic languages (Latin, Oscan, Umbrian, etc.) might well be "areal features". More certainly, very similar-looking alterations in the systems of long vowels in the West Germanic languages greatly postdate any possible notion of a proto-language innovation (and cannot readily be regarded as "areal", either, since English and continental West Germanic were not a linguistic area). In a similar vein, there are many similar unique innovations in Germanic and Baltic/Slavic that are far more likely to be areal features than traceable to a common proto-language. But legitimate uncertainty about whether shared innovations are areal features, coincidence, or inheritance from a common ancestor, leads to disagreement over the proper subdivisions of any large language family.

A sprachbund is a geographic area having several languages that feature common linguistic structures. The similarities between those languages are caused by language contact, not by chance or common origin, and are not recognized as criteria that define a language family.

Mixed language

The concept of language families is based on the historical observation that languages develop dialects, which over time may diverge into distinct languages. However, linguistic ancestry is less clear-cut than familiar biological ancestry, in which species do not crossbreed. It is more like the evolution of microbes, with extensive lateral gene transfer: Quite distantly related languages may affect each other through language contact, which in extreme cases may lead to creoles or mixed languages with no single ancestor. In addition, a number of sign languages have developed in isolation and appear to have no relatives at all. Nonetheless, such cases are relatively rare and most well-attested languages can be unambiguously classified.

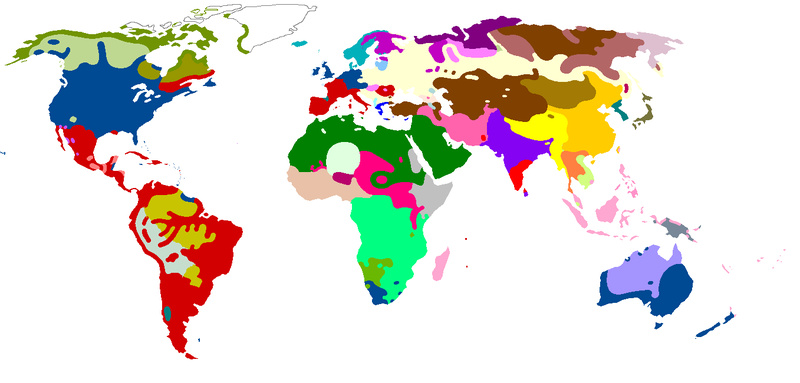

Distribution

|

|

See also

- Auxiliary language

- Constructed language

- Endangered language

- Extinct language

- Global language system

- ISO 639-5

- Linguist List

- List of language families

- List of languages by number of native speakers

- Proto-language

- Tree model

Notes

- ↑ "Ethnologue: Languages of the World, Sixteenth edition", accessed 08 June 2010, ISBN 978-1-55671-216-6

- ↑ Müller, Max (1862). Lectures on the science of language: delivered at the Royal institution of Great Britain in April, May and June, 1861 (3rd ed.). London: Longman, Green, Longman and Roberts. p. 216. "The genealogical classification of the Aryan languages was founded, as we saw, on a close comparison of the grammatical characteristics of each;...."

Additional reading

- Boas, Franz (1911). Handbook of American Indian languages. Bureau of American Ethnology, Bulletin 40. Volume 1. Washington: Smithsonian Institution, Bureau of American Ethnology. ISBN 0803250177.

- Boas, Franz. (1922). Handbook of American Indian languages (Vol. 2). Bureau of American Ethnology, Bulletin 40. Washington: Government Print Office (Smithsonian Institution, Bureau of American Ethnology).

- Boas, Franz. (1933). Handbook of American Indian languages (Vol. 3). Native American legal materials collection, title 1227. Glückstadt: J.J. Augustin.

- Campbell, Lyle. (1997). American Indian languages: The historical linguistics of Native America. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-509427-1.

- Campbell, Lyle; & Mithun, Marianne (Eds.). (1979). The languages of native America: Historical and comparative assessment. Austin: University of Texas Press.

- Goddard, Ives (Ed.). (1996). Languages. Handbook of North American Indians (W. C. Sturtevant, General Ed.) (Vol. 17). Washington, D. C.: Smithsonian Institution. ISBN 0-16-048774-9.

- Goddard, Ives. (1999). Native languages and language families of North America (rev. and enlarged ed. with additions and corrections). [Map]. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press (Smithsonian Institution). (Updated version of the map in Goddard 1996). ISBN 0-8032-9271-6.

- Gordon, Raymond G., Jr. (Ed.). (2005). Ethnologue: Languages of the world (15th ed.). Dallas, TX: SIL International. ISBN 1-55671-159-X. (Online version: http://www.ethnologue.com).

- Greenberg, Joseph H. (1966). The Languages of Africa (2nd ed.). Bloomington: Indiana University.

- Harrison, K. David. (2007) When Languages Die: The Extinction of the World's Languages and the Erosion of Human Knowledge. New York and London: Oxford University Press.

- Mithun, Marianne. (1999). The languages of Native North America. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-23228-7 (hbk); ISBN 0-521-29875-X.

- Ross, Malcom. (2005). Pronouns as a preliminary diagnostic for grouping Papuan languages. In: Andrew Pawley, Robert Attenborough, Robin Hide and Jack Golson, eds, Papuan pasts: cultural, linguistic and biological histories of Papuan-speaking peoples (PDF)

- Ruhlen, Merritt. (1987). A guide to the world's languages. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Sturtevant, William C. (Ed.). (1978–present). Handbook of North American Indians (Vol. 1–20). Washington, D. C.: Smithsonian Institution. (Vols. 1–3, 16, 18–20 not yet published).

- Voegelin, C. F.; & Voegelin, F. M. (1977). Classification and index of the world's languages. New York: Elsevier.